Chartae Socraticae

Chartae Socraticae

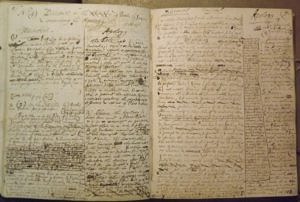

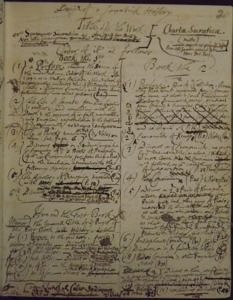

Alongside preparations for an edition of Shaftesbury’s correspondence — our collection to date comprises over one thousand letters, a number of them previously unknown — we have been working, for example, on Shaftesbury’s manuscript draft for the Chartae Socraticae.

Conceived as a companion to “Vertue & Philosophy & ye Antients”, this work would have taken the form of a critical edition presenting those Greek texts which, in the Earl’s opinion, preserve for us the life and thought of the historical Socrates. The original Greek was to be accompanied in each case by an English translation, copious notes, and “Discourses” containing Shaftesbury’s own interpretations, one aim being to introduce readers who have not had the “advantage” of Greek, but “who deserve & are capable of ye Treasures of ye Antients” to Socrates. Dated entries show that the Earl worked on his “Design” over a period of at least five years, but the planned publication was never completed.

The manuscript notes are meticulous and detailed, covering virtually every aspect of the book envisaged by Shaftesbury, and they thus provide us with a fairly clear picture of his intentions. The first part of the book would have presented Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Apology, the texts which, the Earl believed, show us the real Socrates. The second part would have been devoted on the one hand to Xenophon’s more ‘apocryphal’, but still ‘reasonably historical’ Socratic writings, on the other to the ‘fictional’ Socrates as seen in Aristophanes, Plato (both of whom, it was to be conceded, did occasionally offer reliable information too) or, for example, in Lucian and Athenaeus.

The Chartae Socraticae would also have included an “Account of Xenophon”, while the notes on his works would have highlighted the beauty of the Greek author’s style and the intricate, but seemingly negligent structure of his Memorabilia. The admiration for Xenophon which pervades this draft found expression in Shaftesbury’s Soliloquy: “He join’d what was deepest and most solid in Philosophy with what was easiest and most refin’d in Breeding, and in the Character and Manner of a Gentleman. … This was that natural and simple Genius of Antiquity, comprehended by so few, and so little relish’d by the Vulgar.”