Library: Little Doods and Cranston

Shaftesbury, Little Doods, and the Cranston Library

In the summer of 1709 Shaftesbury gave up his home at Little Chelsea — the “Little House and Studdy” which, some nine years earlier, he had modified and furnished according to his own bachelor needs, “with no thoughts beyond a single Life” — and leased a property called Little Doods in Reigate, Surrey. The reasons for this move were two-fold. His “ill Habit of Breathing & the Cause of it (ye Coal Smoak) encreasing”, he wanted a house far enough away from London for him to be able to stay in it during the winter months, but still go from there “on an exigence” to Westminster. In addition, he now needed a residence more suited to his new marital status. His wedding to Jane Ewer, a distant relative on his mother’s side, took place on 29 August 1709, and the couple moved right away into the Reigate house.

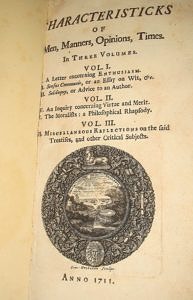

An entry in Shaftesbury’s almanac for 9 February 1711 shows that his only child, the future fourth Earl, was born there “This Night between eleven & twelve”, with a Reigate midwife (Mrs Hailer) among the nine women attending the Countess. One month later, on 9 March, his son was christened at the house by the “The Minister Mr Bird of the place”. Although Shaftesbury and his wife did leave Reigate for Dorset in late July 1710 and stayed at St Giles’s House for an unknown period of time — certainly until the end of August, possibly even until after the parliamentary elections in October — it seems likely that much of his writing from September 1709 to June 1711 was done at Little Doods: Soliloquy, Miscellaneous Reflections, and work on the collected edition of his treatises.

Robert Voitle (Third Earl 299-300) describes the house as he saw it when he visited Reigate, but the building he visited sounds rather different from the Little Doods painted by the artist John Hassell in 1821 (a watercolour now kept at the Surrey History Centre). The earlier building was perhaps torn down in the nineteenth century to make way for the later one, which has itself now disappeared. The older of the two, or more properly its garden became known locally at some point as “The Wilderness”, and there still exists today, on land which may once have been part of the property, a folly sometimes referred to as “Shaftesbury’s Grotto”. Even if it would not be hard to imagine the Earl tending to the layout of his garden, the landscaping there is more likely to have been the work of a later occupant. The following description was published in the fourth, augmented edition of Defoe’s A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, vol. 1 (London, 1748), 251 (in the section on Reigate and not mentioned in the preceding editions):

In this Town the late Lord Shaftsbury had an House; to which he frequently retired, when he was inclined to seclude himself from Company. This House is now possessed by a private Gentleman, who has laid out and planted a small Spot of Ground in so many little Parts, as to comprise whatever can be supposed in the most noble Seats: so that it may properly be called a Model. The Name it passes under by the Inhabitants of Rygate, is, The World in one Acre of Land.

While Shaftesbury’s Little Doods may be long gone and the surviving folly not actually his, there remain a few authentic physical traces of his presence in Reigate. After the Earl and Countess had left England for Naples at the end of June 1711, the business of emptying the house and surrendering the lease was left in part to their steward John Wheelock and to Shaftesbury’s friend Thomas Micklethwaite. Some or all of the books once housed in the library at Chelsea had been taken to Reigate in 1709, and those not now packed and shipped to Naples (as probably only a small selection was) were sent to St Giles’s House. There were, however, four books which stayed in Reigate, passed on as a gift to the Cranston Library.

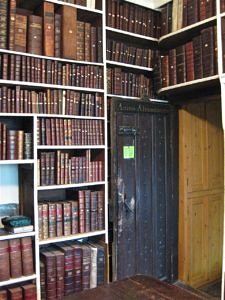

This had been founded in 1701 by the vicar of St Mary’s Church, Andrew Cranston, as a public lending library — the first of its kind in England; it was housed

then as now in a room above the vestry at St Mary’s. By 1705 Andrew Cranston had amassed some 1600 donated books, these covering a broad selection of subjects. The theological gifts accepted were by no means restricted to the non-controversial and seem to reflect the vicar’s own desire for reasoned debate rather than dogmatic condemnation. Examples of this are the books handed in by members of the local Quaker community — one of them Nathaniel Owen, from whom Shaftesbury leased Little Doods — and kept alongside anti-Quaker literature sent at Andrew Cranston’s request by the SPCK (of which he was a correspondent).

Donated items were recorded in a register, and among the benefactors’ names were two men well known to Shaftesbury. John Toland presented five books — two by Rudolf Hospinian and three collections of Socinian tracts — in December 1701, and William Stephens (rector of Sutton in Surrey) donated an edition of John Jewel’s works in October 1702. Earlier gifts to the library include ten volumes from the estate of Philippa Brown, née Cooper (d. 1701), sister to the first Earl of Shaftesbury and resident of nearby Betchworth Castle. After Andrew Cranston’s death in 1708, responsibility for the library passed to a number of trustees, one of them Shaftesbury’s “good Friend” Lord Somers (at the time owner of the manor, but not resident there).

Shaftesbury himself had been represented in the Cranston Library since 1703 with a copy of Benjamin Whichcote, Select Sermons. The donations from the Earl’s own shelves were registered on 3 December 1711 by John Bird, Cranston’s successor as vicar of St Mary’s and the clergyman who officiated at the above-mentioned christening. As Shaftesbury himself was by this time settling into his new home at Chiaia, it is likely that the books were handed in either by Thomas Micklethwaite or John Wheelock. The titles are:

The Tryal of Doctor Henry Sacheverell, before the House of Peers, for High Crimes and Misdemeanors (London, 1710) 2°

The works of the late Reverend Mr. Samuel Johnson (London, 1710) 2°

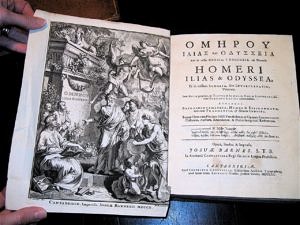

Homeri Ilias et Odyssea […] Batrachomymachia, Hymni et Epigrammata, ed. J. Barnes, 2 vols (Cambridge, 1711) 4°

Creative Commons LicenseCR953 Cooper, Anthony Ashley, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury: Characteristicks. 1711. Corrigenda page with handwritten marginal notes by The Trustees of the Cranston Library is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

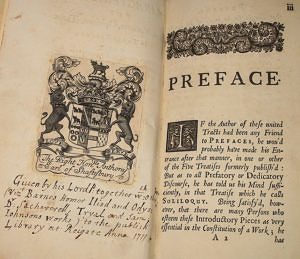

In each is Shaftesbury’s bookplate (with his family’s coat-of-arms) and a note documenting the donation. The first three books possibly came already bound in similar style (leather, with gilt tooling); the Characteristicks, all three volumes bound together in one (leather, no ornamentation) are more likely to have arrived unbound. The very last page (the second of the “Corrigenda”) shows three additional corrections in the margin and three in the text, some in the same hand as the corrections found in the British Library copy of the 1711 text, and all later used in the second edition.

Shaftesbury’s anxious letters from Naples about the preparations for the second edition and his fears that two volumes containing the manuscript fruits of his revision had gone missing may well have prompted his friends in England to start having extra copies made of the planned changes. Ultimately, however, the story behind the Cranston Characteristicks must remain a mystery.

We are much indebted for the above to Alan Moore for information on Little Doods, and to the present trustees of the Cranston Library, especially Hilary Ely, who has provided us with the photographs, and Andrea Thomas, who has collected fascinating details (many more than we can show here) on the Shaftesbury-Reigate-Cranston connection. If you would like to know more about the library, please contact cranstonlibrary@gmail.com.